[Over the last year-plus, I’ve done a lot of thinking, writing, and speaking about the so-called anti-ESG movement. It’s a complicated thing. This is my attempt to wrangle some kind of framework around the various critics out there. It appeared in HBR last month.]

When I speak with business leaders about corporate sustainability, the conversations now inevitably turn to the “anti-ESG” movement — a loosely defined collection of beliefs and actions aimed at fighting a perceived shift towards “woke” or progressive ideas in society and business.

While some of the rhetoric may be cooling a bit, external critics of ESG have definitely altered how companies act, especially in the U.S. Executives have gotten quieter about their sustainability efforts (also known as “greenhushing”). Has the pullback on talking about climate and equity issues slowed action within companies? It’s not clear yet, but the public pressure to keep your head low doesn’t encourage a broad transition to more sustainable practices and brands.

In working with organizations, I see executives — from the CEO on down — struggling to avoid being a target, while staying true to their values and public commitments. They know customers, employees, and other stakeholders are watching. But it’s hard to be strategic about something as amorphous as “anti-ESG.” There is no single anti-ESG movement, and many voices are at odds. Some critics oppose sustainability entirely, while others support it but are deeply skeptical of corporate claims (especially from banks about ESG investing).

We need a more nuanced approach to address these pressures. I propose a model to help company senior leadership and managers understand the various voices and guide how to engage with them.

What We Mean When We Talk About ESG and Sustainability

First, some quick definitions. For me, “ESG,” which stands for environmental, social and governance, mainly refers to the investor-led movement to understand how social and environmental issues create risk for a business. It’s about helping investors assess a company as an investment. ESG also refers to a fast-changing area of corporate financial reporting, as mandates to disclose material environmental and social risks are multiplying. Meanwhile, “sustainability” covers a much broader perspective on a company’s role in society, whether it’s operating within the limits of the planet, and how it helps (or doesn’t) solve major environmental and social challenges. But the two ideas are constantly conflated, which causes confusion.

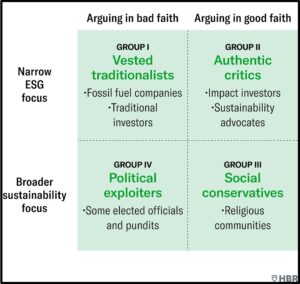

To help corporate leaders navigate the diverse anti-ESG and anti-sustainability voices, I’ve tested out a simple framework with clients. I map the voices along two dimensions in a classic 2×2 grid. One axis assesses the breadth of the criticism — are the critics focused primarily on how the financial world uses the term ESG, and how companies respond to investor questions? Or are attacks on compan ies a proxy for a larger battle against the full sustainability agenda (perceived by some as inherently liberal or progressive)?

ies a proxy for a larger battle against the full sustainability agenda (perceived by some as inherently liberal or progressive)?

The other axis evaluates whether the critics — of ESG or sustainability in general, or of your company specifically — are arguing in good faith. Do they believe what they say? Are they interested in solving issues and improving society’s well-being? Or are they more cynical, just hoping to “win” (or make others lose)?

These two dimensions create four boxes of players. With the caveat that there’s clearly overlap and blurry lines, let’s look at the groups. We’ll start with two somewhat easier ones, then dive into the more complex groups that take up all the oxygen.

I. Vested traditionalists (ESG focus, in bad faith)

For some, the rise of ESG funds is a threat. They don’t want to see the world use the leverage of finance and reporting to address shared challenges; it would reduce their power. This is mainly two groups: 1) fossil fuel companies that are being screened out of funds and want to slow action on climate change; and 2) some traditional investors, steeped in shareholder primacy and obsession with short-term profits, who don’t care if ESG makes sense. These groups want to continue making money the way they know how.

How to handle this group

Companies will feel pressure from these groups through industry organizations and value chains, or through their investor base. If sustainability is a priority to your business, then the larger play is to change the mix of investors, seeking out those with a longer-term view, such as institutional investors. In parallel, keep making the business case for action on environmental and social challenges — you may convert some to see that over time, sustainability and business value are interdependent, not at odds. With industry peers or partners who cast doubt, stick to your guns about what you expect from them.

II. Social conservatives (sustainability focus, in good faith)

Some people want a more traditional approach to big social issues. They may be uncomfortable with the growth in rights for the LGBTQ+ community, for example, or, most pointedly, feel strongly pro-life. Many people, including many employees and stakeholders, have personal religious objections and are acting in good faith.

How to handle this group

There is no easy answer. Yes, companies should listen to a range views and voices, and allow critics to speak their minds. But most large companies have made diversity and inclusiveness core values, and they are actively reaching out to these communities as potential employees and customers. LGBTQ+ employees (and their allies) who feel their rights are being restricted need to know you have their back.

After the U.S. Supreme Court Dobbs decision, which eliminated a federal right to abortion as part of reproductive care, many large companies told their employees that they would cover travel expenses to states that still provides these services. They made no secret of the position, but didn’t make a big public statement either. A key element of being a sustainable company, with justice and equality as goals, is consistency. If you have made clear what you stand for, then stick with those values, especially in communications with your employees — even if you don’t make a big deal about it outside the company.

Now, for the groups that companies most acutely feel pressure from.

III. Authentic critics (ESG focus, in good faith)

ESG funds, in general, are vehicles that claim to screen companies on environmental and social dimensions. In parallel, regulators and influential organizations are rapidly changing the requirements for company disclosures on ESG, with a special focus on climate change. Investment in ESG funds surged for years, though more recent factors, including global geopolitics shifts favoring fossil fuel stocks (which are underweighted in ESG), have slowed inflows. Still, there are hundreds of billions just in ESG versions of one major investment class, exchange-traded funds (ETF).

There are good faith, authentic critics swarming these efforts. They are pro-sustainability in the broader sense, so they are pushing companies making ESG claims to be clearer and to do more.

First, a few insiders have publicly called out what they see as greenwashing. ESG investment vehicles, they say, don’t screen companies in any way that ensures positive outcomes for people or planet (i.e., real sustainability). As demand for more sustainable or “impact” funds grew, the financial community rushed to create products, labeling them ESG funds, but without real guidelines, standards, or definitions backing them up. Inventing new assets with overpromises is unfortunately nothing new — remember those junk mortgage-backed securities that were somehow AAA rated. But to the authentic critics, it’s egregious to promise good returns and say you’re saving the world with little to prove it. Point well taken.

A related group of critics has targeted the extensive work on ESG reporting. The effort to create consistency in how companies report to investors and other stakeholders is currently in a state of chaos. In addition to the regulators and standards bodies working on the problem, companies are already answering a stream of questions from private ratings groups, many of which are not driving sustainability. For example, an executive at a global retailer told me that a ratings group asked, “Do you use a lot of energy?” which is less than useless. Of course, a giant company uses lots of energy. It’s more on point to ask about carbon intensity, absolute emissions, use of renewables, and so on.

Some key organizations are trying to create a common, harmonized reporting structure — most notably the International Sustainability Standards Board, run by the IFRS Foundation. In theory, the ISSB, which also manages the International Accounting Standards Board promises to make sustainability reporting as consistent as financial reporting.

But, as the authentic critics point out, harmonized doesn’t mean useful. New requirements need to be based in a “thresholds view” of the world — meaning, the rules should drive companies to operate within the bounds of the planet (like science-based emissions reductions) or actively build an equitable world. While some progress is better than none, and standards will evolve and improve over time, this more purist view is based in the practical realities of our big, growing challenges.

How to handle this group

To help satisfy the critics of the new rules, companies should listen and engage in the creation of these standards and regulations. This means being part of open dialogues and comment periods on new laws — and doing it in good faith as well.

While standards evolve, stakeholder questions will proliferate, and companies will need more people working on the problem. One large consumer products company has a full-time person in the CFOs office working on sustainability reporting. That’s just the beginning of what will be a large expansion of organizational skills and resources to handle new reporting requirements.

As for answering the critics of ESG investing specifically, fund creators and asset buyers should engage and listen. The financial players should clarify in more detail how these funds and investment strategies are defined, and whether they screen not just on risk to a company, but also on global risks stemming from the company (so-called “double materiality”). And avoid overpromising.

IV. Political exploiters (sustainability focus, in bad faith)

Finally, we have the group that gets the most attention: The political actors (individuals, coalitions, interest groups, and pundits) who publicly criticize “woke” companies and pursue mainly regressive legislation. A recent, high-profile example of this is Florida’s ongoing battle with Walt Disney company over the state’s so-called “don’t say gay” bill. Under pressure from Disney employees, the then-CEO spoke out against the legislation. In response, the governor and his state legislature came down on the company, reducing some long-standing tax breaks and development incentives.

The pressure on companies to avoid being seen as “woke” comes from many places, especially social and traditional media. When companies like Mars (M&Ms), Budweiser, and Target came under fire for supporting the LGBTQ+ community, viral videos pushed for boycotts. Sales for some of these products or companies have suffered, but did conservative boycotts work, or did LGBTQ+ supporters reduce spending because of the way the companies mismanaged the situation? It’s likely both, which would argue for picking a lane and sticking with it.

How to handle this group

To say this is thorny is an understatement. Disney has since pushed back pretty hard, but the company’s struggles points to one of the solutions — work with others. Had Disney organized a coalition to speak out against the bill, it would’ve been harder for the state to retaliate; taking on many firms at once would be impractical and politically risky. Working together, with collective courage, sends a clearer message and has more impact. In one notable example from some years ago, more than 100 CEOs signed an open letter against what they believed was an anti-LGBTQ law in North Carolina. It helped — the state rolled back the law.

But the real challenge here is that on many of the biggest issues that directly affect your stakeholders and your ability to do business in the future — in my view, these might include climate, income inequality, racial justice, abortion rights and women’s bodily autonomy, and LGBTQ+ rights — you can’t sit it out. Some companies, such as Chick-fil-A and Hobby Lobby, have chosen a more socially conservative path and are staying on it. But companies that choose to say nothing in these cases are still saying something, especially to your employees. Most big companies have stated values and commitments in support of some, if not all, of these issues — and not living up to their statements is risky for the business.

Of course, companies don’t want to make anyone angry. But on many major topics, that ship has sailed. Some people will be unhappy either way, so do what fits the values of the company and what seems right. Be consistent. And don’t give in to bullies, even if they’re dangerous, like those who called in bomb threats to Target stores over gay pride merchandise.

A final thought on the authentic critics and the political exploiters. These two groups are often cast in overly simplistic terms, using the “both sides” logic of the media. The story is that one group wants conservative outcomes, the other more liberal. While an easy shorthand, it’s not quite true. For example, the Indiana Bankers Association and the Indiana Chamber of Commerce — which nobody would confuse with progressive groups — are fighting Republican state legislators who are trying to restrict the creation of ESG funds. And the pro-sustainability authentic critics who call out ESG greenwashing or push for better standards are not generally political.

The false both-sides narrative also radically understates the power differential of these groups. Authentic critics mostly write articles, post in social media, and show up to influence the design of regulatory and reporting systems. It’s soft power at best. The political exploiters include governors, secretaries of state, attorneys general, and legislatures. They are passing laws that have profound impacts on your employees’ and customers’ lives.

—-“If ESG becomes toxic as a phrase…It doesn’t matter to me.

I’m just gonna stop saying ‘ESG’”

— James Quincey, CEO, Coca-Cola

Keep Your Eye on the Prize

I believe that despite attacks on ESG and sustainability, the trajectory of action on our big issues won’t truly change. There are compelling reasons to keep going. It’s good for business, and the megatrends driving it all — like a changing climate, rising inequality, younger generations expecting more commitment to sustainability, and exponential reductions in the cost of clean technologies — are accelerating.

The best advice I can give is for companies to keep their eye on the prize: building better, more resilient businesses that profit by helping solve big challenges and contributing to a thriving world. Smart CEOs seem to get this. “I’m a CEO who understands what brings value… Sustainability matters to our employees from a recruiting standpoint, it matters to our clients, it’s part of our regulatory landscape, it matters to consumers,” says Julia Sweet, CEO of Accenture. “That’s not changing because of what politicians want to call it.” Coca-Cola CEO James Quincey adds, “If ESG becomes toxic as a phrase…It doesn’t matter to me. I’m just gonna stop saying ‘ESG’…My business strategy is constant and clear and centered around the business and the things that consumers care about and that fix societal problems. If people want to attach labels to it, that’s their issue. I’m saying that business will be great if I fix these problems, and it will be good for shareholders and be good for society.”

In the end, you’ll benefit from engaging with critics who operate in good faith, and you can’t ignore those who are less noble in their aims. You’ll need some responses ready on the big issues. Just don’t let the noise stop you from doing what’s right for the business and society.

(Photo: fizkes, iStock-1138947312)

——————

If you enjoyed this article, please pass it on.

Subscribe to get all of Andrew’s articles in your in-box.