[I posted this last month for my MIT Sloan Management Review column, here. The real question now is, Will these companies continue to withhold money from politicians that undermine democracy? It’s a good sign that big Georgia-based companies — Coca-Cola, Aflac, Delta Air Lines, Home Depot and UPS — came out a couple days ago against the state legislature’s blatant (and racist) attempts to suppress minority voting. Companies are increasingly engaged in protecting the pillars of society, like democracy, fact, and science. It’s good to see.]

After the attempted coup and attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, many companies quickly made a rare move: They cut donations to politicians. Dozens of multinationals started by pausing all political donations. A subset — the more courageous and honest companies — have declared that they will not give any money to the 147 U.S. congressional representatives and senators who voted to overturn the normally ceremonial Electoral College vote count.

Starting with Blue Cross, Dow, Marriott, and a few other first movers, the growing list now includes Airbnb, Amazon, American Express, AT&T, Cisco, Citi, Comcast, Disney, Exelon, GE, Goldman Sachs, Intel, Kraft Heinz, Mastercard, Morgan Stanley, Nike, Oracle, Pfizer, State Street, Walmart, and Verizon. In other words, this is not the usual tiny list of progressive companies like Patagonia that put pressure on governments to pass more aggressive environmental laws. This is something new. And it is no small monetary issue — companies have given at least $170 million to those 147 legislators over the past four years.

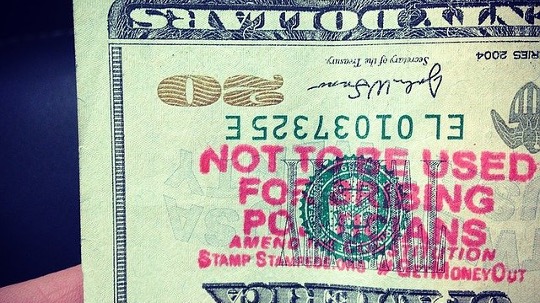

For Europeans, the move to take money out of politics doesn’t seem impressive. In most developed countries, a combination of contribution limits, bans on TV advertising, and public financing of campaigns makes it useless or impossible to throw money at politicians. But the U.S. is a different story. In 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court decision Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission “reversed century-old campaign finance restrictions and enabled corporations and other outside groups to spend unlimited funds on elections,” according to the Brennan Center for Justice. In a 5-4 decision, justices equated political spending with free speech.

The case released a torrent of money by large political action committees (called super PACs), which can run as many ads for or against candidates as they like. The flow of “investment” in candidates running for office has been astounding. The Center for Responsive Politics collects public information on political donations and posts analyses on its website, OpenSecrets.org. It calculated that in 2010, super PACs spent $63 million. By 2020, that figure was $2.1 billion.

The result has been even more centralized power and increasing inequality. The top 1% of donors gave 93% of the money, with just 100 people providing 70% of it. The U.S. has what is, essentially, legalized corruption that gives outsize influence to the wealthy and powerful. What in other countries is done in back rooms and with envelopes slipped under the table is aboveboard in the U.S.

But apparently, armed insurrection finally made many large companies uncomfortable with supporting politicians just because they’re in power. It’s been a whirlwind of organizations changing course. Most large companies have spent decades saying, “Oh, we’re not political,” all while pouring money into politicians’ coffers to exert influence on everything from trade policy to regulatory strategies.

Some sectors have tilted more to one party than another, with law firms and consultancies giving more to Democrats, and oil and gas, auto manufacturing, and big agriculture giving far more to Republicans. Sectors also lean to one side on specific issues. For example, in the case of climate change, only the vested interests (fossil fuel companies) spend targeted money and time lobbying in the halls of power. That said, most big companies have long, and happily, given money to power players in both parties.

Clearly, something is different now. The idea that companies are responsible to the world around them only for their direct (or indirect) operational impacts has been fading fast. The year 2020 was quite a turning point. The murder of George Floyd and the new energy behind the Black Lives Matter movement forced all organizational leaders to look in the mirror. Many felt the need to say something about how they would address racial injustice. Public statements and commitments were mostly focused on operational changes in hiring, promoting diverse executives, or spending money with more diverse suppliers.

Now, with the events of early 2021, many companies have gone public with commitments about their political spending, opening themselves up to more attention and scrutiny about who and what they support. They’re clearly taking this seriously. The New York Times reported that Citi’s head of government affairs wrote in an internal memo that the financial giant “will not support candidates who do not respect the rule of law.”

So if companies are taking into account a politician’s basic commitment to truthfulness and democracy, we can logically ask what else they’ll look at. How about voting records on other critical issues, like climate change, economic inequality, or immigration? These are not idle questions. Solving our biggest challenges requires the private sector and government to work together. Business needs the right politicians who support the right policies.

For example, many companies have committed to vast reductions in carbon emissions and investments in renewable energy. The market can handle some of that, but in reality, government investment in infrastructure is equally necessary to build a multitrillion-dollar clean grid and transportation system. The government must also take the lead by moving more quickly to put a price on carbon emissions. But in the U.S., almost all Republicans at the federal level have never voted for pro-climate policies. How can companies with big climate goals and products that serve the clean economy keep supporting actors who continually vote against their interests?

Or consider living wages. It’s difficult for companies reliant on low-wage workers to unilaterally raise paychecks by themselves; they may put themselves at a net disadvantage if their peers don’t follow suit. Besides, companies that need a thriving global middle class to keep their businesses growing — which is almost all retail and consumer products companies, at the very least — depend on all people being paid enough to buy essentials and more. Only the government can regulate wage minimums.

The point is that major corporations have been knee-deep in political influence for decades. Pretending otherwise is absurd. It’s time for advocacy that does not serve just narrow interests — like reducing a particular regulation for just your company’s sector — but aims for a broader social good. Working with government to move toward shared goals can and should happen. But that requires having the right partners in power positions.

The brave companies cutting funding to politicians who attempted to overturn the results of a free and fair presidential election have made an important leap. As consumers, employees, community members, and investors, we can support these organizations. We should also encourage businesses to go further and ask a simple question: Are the politicians you support blocking progress on our biggest challenges, or are they helping us build a better world?

__________________________

Follow Andrew on Twitter

Subscribe to Andrew’s Blog